How to tell good stories to your kids in support of their mental health

A guide on how to tell good stories to your kids that will support their mental health and help them make sense of the world by Connor McClenahan

Storytelling is powerful for kids and their mental health

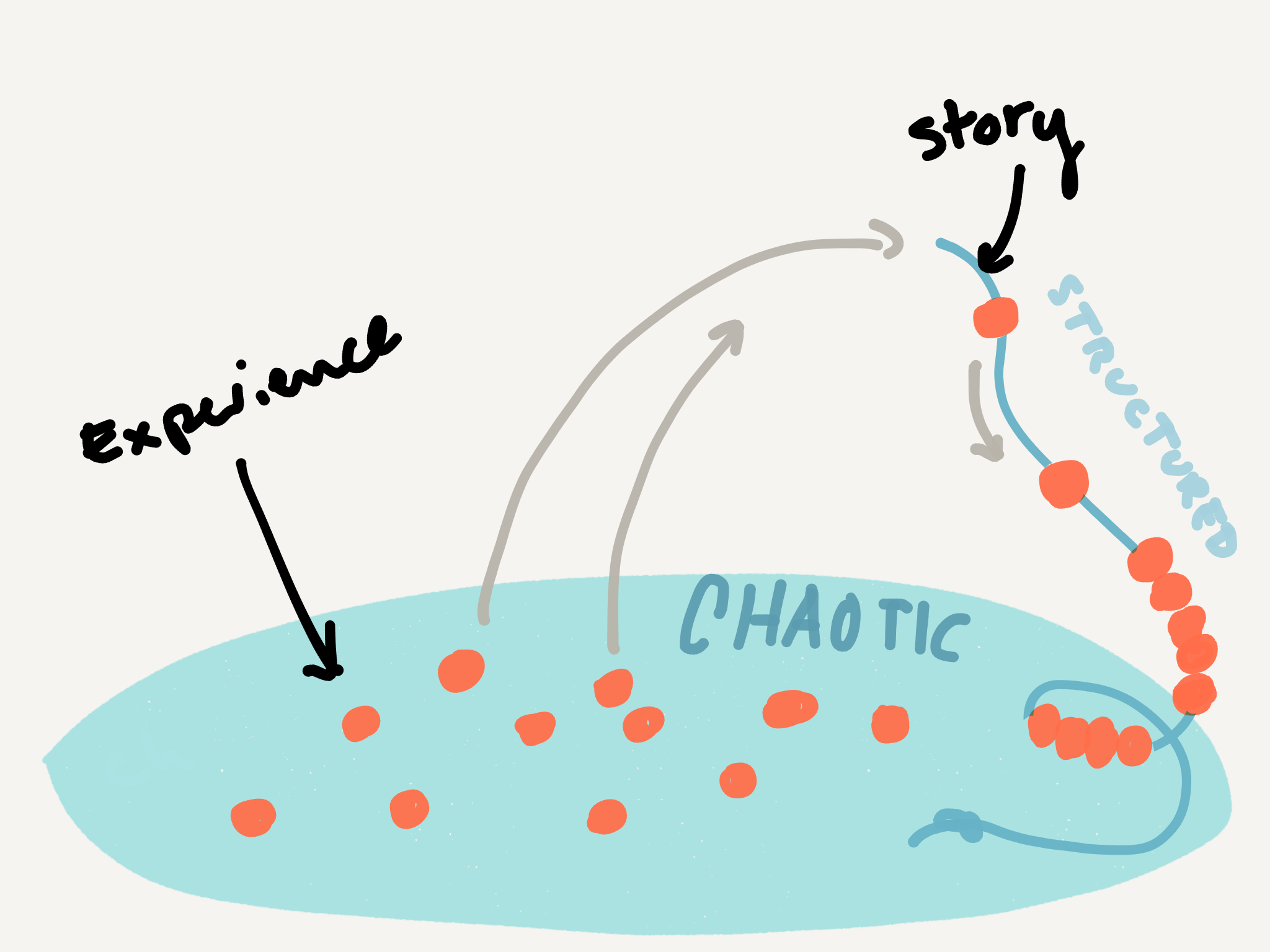

Like making a beaded necklace, the mind continuously strings together bits of information to create a cohesive story that makes sense of the world. How we do this is shaped largely by our earliest relationships. It happens when we first skin our knee. We run to our parents, confused, and hear, “Oh, no! You were running, then you tripped on a rock and fell down! You hurt your knee!”.

When the parents tell the story, they teach the child how to make sense of their pain – they string the beads together for the child to create a “necklace” (story) they can use. It’s these moments that teach us who we are and in what kind of world we live.

Doing Storytelling badly can be harmful to your kids’ mental health

Now let’s talk about what can go wrong. Parents can either not tell the story, or tell a destructive story. First, imagine the child left alone, trying to string the beads, but left with a mess instead. This “mess” is unprocessed pain, and it happens when the child is unable to make sense of overwhelming events. The parent may not help the child because they are afraid or unaware. Instead of being organized and understood, these experiences are chaotic and dissociated.

Second, sometimes the way we practice storytelling can be another source of pain for our children. Imagine a parent who strings the beads together for the child to make a necklace for themselves, instead of the child. With the skinned knee example, we may paint ourselves as the victim, instead of the child: “When are you going to learn? Can’t you see we’re late?” While this form of storytelling may help us to structure our own emotions, it leaves the child’s pain unprocessed.

Telling stories is a tool

When done well, storytelling serves as a powerful tool. A child who is able to process their emotion is able to be fluid and present in challenging situations. They are not as easily overwhelmed, but have better confidence to enter into their own and other’s experiences. This is a tool worth investing in! I want to give a couple of tips for how to tell stories with children that will help them thrive.

When to practice storytelling

Look for:

- Strong emotions. When you see your child being overly upset, sad, afraid, or even happy, you might see these as cues to tell a story with them. This is because emotions are the driving force of our mental world. When we have strong emotions it’s like the “beads” are bouncing all over the place!

- Perseveration. You might find that after your child happens to see a movie too mature for her, she will repeat a certain scary part over and over and over again. She’ll repeat the words, she’ll pretend play, she’ll have dreams about it – like she’s stuck on a broken record. It can be tempting to try to distract her or tell her to “stop it”. However, we might also look at her perseveration like a child who can’t fit a bead on the string, who keeps trying and trying. These are perfect moments to tell the story with them.

- Pain. Even when your child isn’t emotionally upset or perseverating, a good time to tell the story is whenever you guess they might have been hurt. One example might be seeing another child push yours on the playground, but when they come back they don’t say anything. Paying attention to these times teaches our children that these moments matter to you and to them.

How to tell good stories to your kids in support of their mental health

- Focus on the feeling. Because emotions are a the center of our mental life, it’s good to tell a story rich with feeling language. Include what your child appeared to be feeling, as well as what you or others might have been feeling too.

- Tell a good story. A good story has a beginning, middle, and end. It might include the happenings leading up to an event, then an ending that resolves the conflict or tension. Sometimes endings can be difficult to think of, but it’s important to include some form of resolution that helps the child see that the overwhelming event wasn’t the end of it. A good ending will be like tying a knot at the end of the beaded necklace, creating a definitive end-point. Using the skinned knee example, you might include the moment the child was comforted: “Then you ran to mommy! Mommy hugged you, then took you inside and put a bandage on your knee. That helped you feel so much better!”

- Use make-believe. This can be fun. At the end of the day, see if, while playing with your child or telling them a make-believe bedtime story, you can include themes from the story you’ve created. You might have a doll skin their knee, cry out, and invite your child to be the parent who comforts and puts a bandage on. You might also tell a story about a dragon who skinned his knee and needed to ask for help making it better.

How to tell stories to work through difficulties with your kid

As we are talking about telling stories, I’ll offer a story of a parent who learned how to tell stories with their child. This example centers on a conflict that involves anger between a mother and child, which can add another layer of complexity. It can sometimes be easier to talk with a child when the object of their frustration is someone else! However, many of us experience this kind of conflict more than we’d like.

Mary and John: a difficult situation

One day Mary was making lunch for John, her 4-year-old child. As she made his sandwich, she was also feeling stressed about something her mother had said to her across the Thanksgiving table. She’d likely have to confront the situation again over Christmas. Mary put the sandwich down in front of John, who was busy playing with his cars at the table. “Ok, time for your sandwich.”

“I don’t want that – it’s GROSS!” John yelled back. He pushed the sandwich away to make room for his cars to race again. She pushed it closer to him again, knocking one of his cars off the table. “HEEY!” John yelled back, then pushed the sandwich off the table.

Mary’s temperature was rising. She clenched her fists and stormed out of the kitchen. Images of her mother at the Thanksgiving table raced through her head.

Mary took a deep breath, and thought again of John. “I don’t want to treat him the same way my mom treated me.” Mary returned to the kitchen and told the story, to find John with his arms crossed, sitting under the table. Mary sat on the floor next to the table and took another deep breath.

Mary and John: how storytelling can be used to resolve conflict

“We got pretty angry back there didn’t we? You came in here with your cars hoping to play with them. I saw you racing them around and having fun! Then, right as you were racing your cars, I put the sandwich in the middle of the race track. You must have been so frustrated. Is that right?”

“Hmph.” John still had his arms crossed.

Mary continued. “Yeah, you were frustrated. You pushed the sandwich away, and then I got frustrated and moved it back, pushing your car off the table. Then you got mad and pushed my sandwich off. That’s when I left to calm down.”

“Why did you leave?” John replied, still upset.

“I hear that was hard for you, Johnny. I felt angry and I left to calm down so I can work this out with you. Then I took some deep breaths, and then I came back here to sit down with you.”

Later that afternoon, Mary was playing pretend with John. John was making “pizza” and brought some to Mary, who didn’t want to eat. Mary used this time to work out some other ways they could have both handled the situation. Mary played the child who was upset, and she watched for what ideas John had for how to feed her.

Do you have more questions on how to tell good stories to your kids in support of their mental health?

While this is a rough sketch, I hope it helps illuminate how storytelling can be used to move us through painful situations. Because each parent-child relationship is unique, it’s important to try and try again to see how to incorporate this tool in your child’s life.

An article like this might be leaving you with more questions than answers. Is my child ok? Am I doing a good job as a parent? How did my parents handle my emotions? How does that affect my parenting? These questions are best explored within a safe relationship. If you feel stuck, give me a call (323-580-6711) and let’s talk how to help you move forward.